Ruling out the possibility of the extra-terrestrial origin of a mysterious six-inch skeleton discovered in Chile, scientists have found that it was of a female, likely a foetus, who had a rare, bone-ageing disorder.

Discovered more than a decade ago in an abandoned town in the Atacama Desert, the mummified specimen, nicknamed Ata, started to garner public attention after it found a permanent home in Spain.

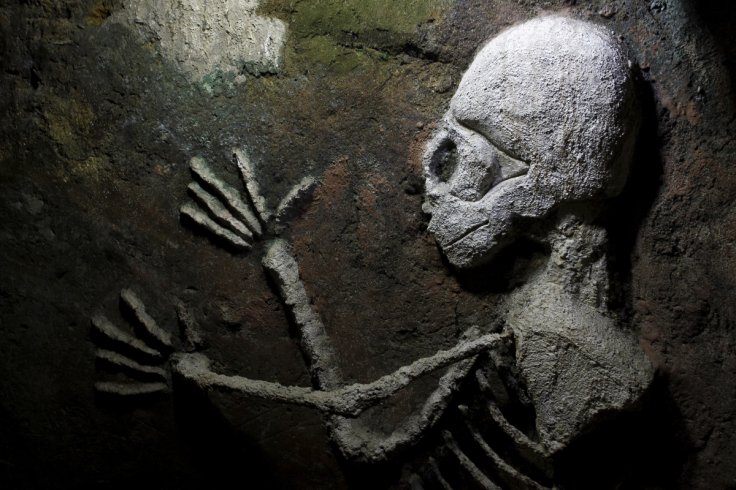

Standing just six inches tall with an angular, elongated skull and sunken, slanted eye sockets, the Internet began to bubble with other-worldly hullabaloo and talk of ET.

But the analysis by Stanford University School of Medicine scientists suggests that Ata was without doubt a human.

This was the skeleton of a human female that had suffered severe genetic mutations, according to the study published in the journal published in the Genome Research.

Ata, though most likely a foetus, had the bone composition of a six-year-old, an indication that she had a rare, bone-ageing disorder, the study found.

To understand the genetic drivers at play, the researchers extracted a small DNA sample from Ata's ribs and sequenced the entire genome.

The skeleton is approximately 40 years old, so its DNA is modern and still relatively intact.

Moreover, data collected from whole-genome sequencing showed that Ata's molecular composition aligned with that of a human genome.

Wile a small percentage of the DNA was unmatchable with human DNA, that was due to a degraded sample, not extraterrestrial biology, said one of the researcehrs Garry Nolan, Professor at Stanford.

The genomic results confirmed Ata's Chilean descent and turned up a slew of mutations in seven genes that separately or in combinations contribute to various bone deformities, facial malformations or skeletal dysplasia, more commonly known as dwarfism.

Some of these mutations, though found in genes already known to cause disease, had never before been associated with bone growth or developmental disorders.

Knowing these new mutational variants could be useful, Nolan said, because they add to the repository of known mutations to look for in humans with these kinds of bone or physical disorders.

"For me, what really came of this study was the idea that we shouldn't stop investigating when we find one gene that might explain a symptom. It could be multiple things going wrong, and it's worth getting a full explanation, especially as we head closer and closer to gene therapy," said study co-author Atul Butte of the University of California-San Francisco. (IANS)