Scientists working on a US Army project have used bacteriophage, a virus that infects and replicates within bacteria, to kill the single-cell organisms through a mechanism different than antibiotics, a new paper has said.

Antibiotic resistance, termed as one of the most dangerous health concerns by the World Health Organisation (WHO), can now be combatted by using phage that can target specific strains, making them an appealing option for potentially overcoming multidrug resistance, said a statement from Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

"This is a crucial development in the battle against superbugs as finding a cure for antibiotic-resistant bacteria is particularly important for soldiers deployed to different parts of the world where they may encounter unknown pathogens or even antibiotic-resistant bacteria," stated Dr James Burgess, program manager at the Institute for Soldier Nanotechnologies, Army Research Office, an element of the US Army Combat Capabilities Development Command's Army Research Laboratory.

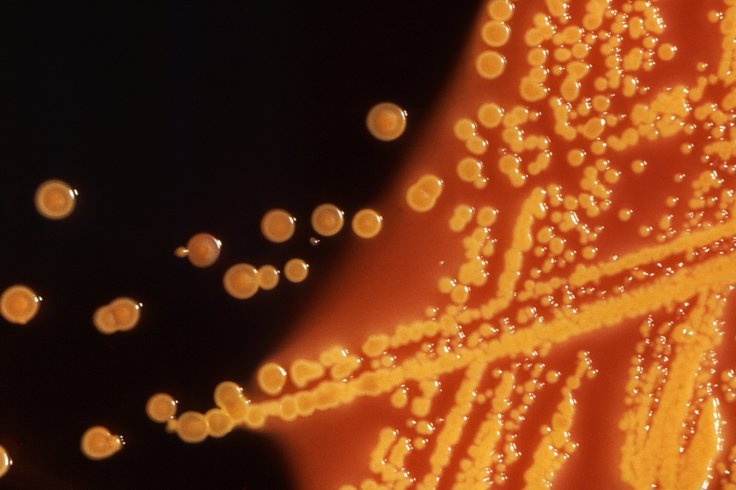

The study published in journal Cell showed bacteriophages could be programmed to kill different strains of E. Coli by making mutations in a viral protein that binds to host cells.

These engineered bacteriophages were also less likely to provoke resistance in bacteria – an increasing problem for public health, said Timothy Lu, lead author and MIT associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science, as well as, of biological engineering.

Lu said that his team created several engineered phages with about 10 million different tail fibres to kill E. Coli grown in the lab, and one of the newly created phages could also eliminate two E. Coli strains resistant to naturally occurring phages from skin infection in mice.

Researchers in 2015 had used a phage from the T7 family, which naturally kills E. Coli, to target other bacteria by swapping in different genes that code for tail fibres.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has also approved a handful of bacteriophages for killing harmful bacteria in food, but they are not used to treat infections because finding naturally occurring phages to target the right kind of bacteria is difficult and time-consuming.

Lu explained these phages were a "good toolkit for killing and knocking down bacteria levels inside a complex ecosystem in a targeted way" as one of the ways E. Coli could become resistant to bacteriophages was by mutating LPS receptors so that they were shortened or missing, but his team found that some of their engineered phages could kill even strains of E. Coli with mutated or missing LPS receptors.

"Being able to selectively hit those non-beneficial strains could give us a lot of benefits in terms of human clinical outcomes," he added.