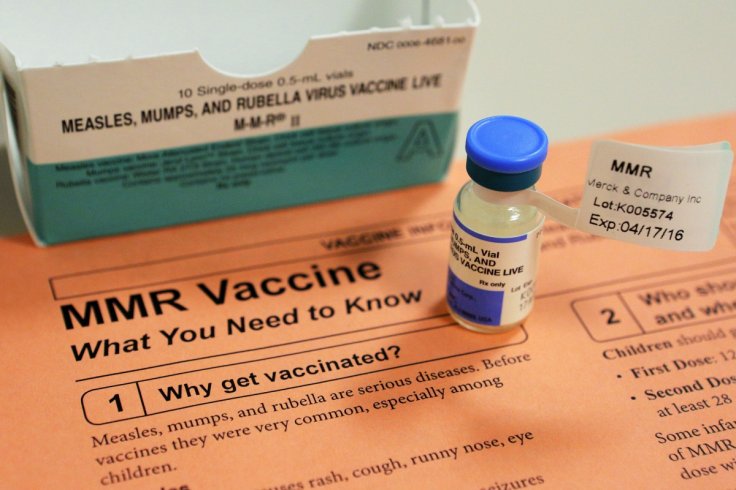

Research shows that measles eliminates 20 to 50 percent of antibodies posited against a collection of viruses and bacteria. It lowers a child's immunity. So if the immune system is impacted by the measles, it has to 'relearn' how to protect the child.

This 'immune amnesia' that is developed by the body can be prevented by vaccinations, suggest researchers. Even post infections, patients can gain from booster shots of early childhood vaccines.

For a decade, researchers found that the measles vaccine protects the body from the rash-like fever with spots and also from other infections over time. Some scientists have suggested that the vaccine gives a general boost to the immune system. The protective shield is due to its effect of preventing measles infection.

Hence, while the virus can impair a body's immune memory, leading to immune amnesia, the vaccine can work to put up a protective shield against measles infection. Hence, the vaccine can prevent the body from "forgetting" its immune memory and keeping up a resistance to other infections. Study shows that immune amnesia and suppression might last a couple of years or more.

The study by a global team of researchers at Harvard Medical School, Brigham and Women's Hospital and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health gave some answers. Reported in Science, the research shows that the measles virus can remove 11 percent to 73 percent of various antibodies protecting against viral and bacterial strains that a patient was earlier immune to. The collection can include a range of infections from influenza to herpesvirus to bacteria that cause pneumonia and skin infections.

Hence, measles virus could destroy half the antibodies a person has against chicken pox, for instance. The shield might get even weaker if many of the antibodies that have been lost are strong defenses, called neutralizing antibodies. "Imagine that your immunity against pathogens is like carrying around a book of photographs of criminals, and someone punched a bunch of holes in it," said the study's first author, Michael Mina, a postdoctoral researcher in the laboratory of Stephen Elledge at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital at the time of the study, now an assistant professor of epidemiology at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

"It would then be much harder to recognize that criminal if you saw them, especially if the holes are punched over important features for recognition, like the eyes or mouth," said Mina.

Research into the immune damage brought about by the measles virus and pointing out the value of preventing the infection through vaccination has helped to shed an important light into the scope and reach of the disease.

"The threat measles poses to people is much greater than we previously imagined," said senior author Stephen Elledge, the Gregor Mendel Professor of Genetics and of Medicine in the Blavatnik Institute at Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women's Hospital. "We now understand the mechanism is a prolonged danger due to erasure of the immune memory, demonstrating that the measles vaccine is of even greater benefit than we knew."