In a path-breaking scientific endeavour, researchers have taken the first-ever pictures of the base of the Thwaites Glacier on the oceans' floor in Antarctica, capturing how the glacier contributes to the rise in sea levels. The amount of ice flowing into the sea from Thwaites has doubled in the last 30 years.

The Thwaites Glacier is responsible for four percent of the rise in global sea levels. A peaking in its foundation could cause the glacier to give way and lead to sea-level rise up to 25 inches, say scientists. The images, taken by an underwater robotic vehicle, recently contributed to a larger data collection by the International Thwaites Glacier Collaboration (ITGC). This will help analyze how Antarctic glaciers contribute to sea-level rise.

Antarctica has the largest body of ice on Earth and "will contribute more and more of sea-level rise over the next 100 years and beyond. It's a massive source of uncertainty in the climate system," said Britney Schmidt, an ITGC co-investigator from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

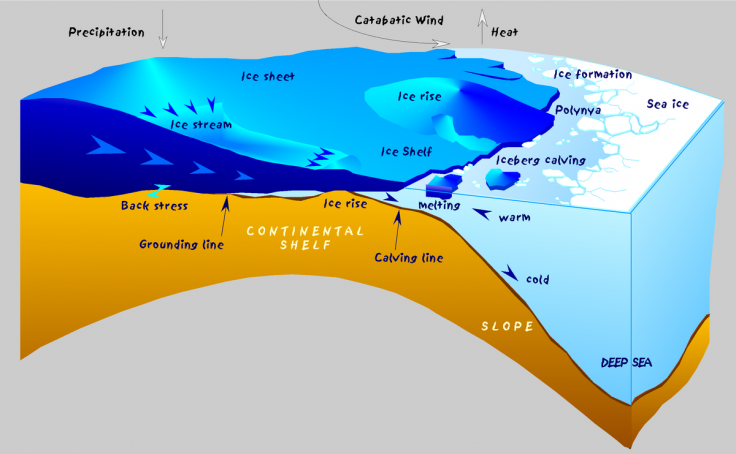

Reaching the grounding line

The underwater probe inspected what is known as the grounding line that lies between the point where the glacier is based on the ocean floor and where it floats above the water. The steeper and deeper it is, the faster the ice flows into the ocean. Hence, the area is important to keep the glacier stable.

This is the first time scientists could explore the grounding zone of a major glacier under the water, where the greatest degree of melting and destabilization can occur, explained Schmidt.

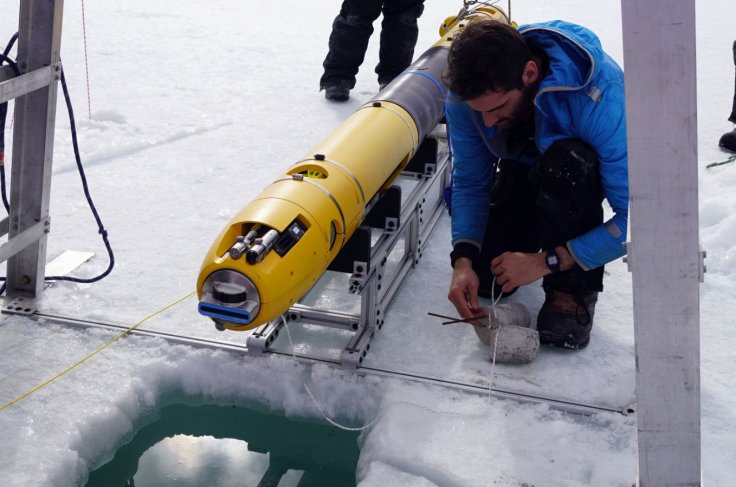

Icefin—The underwater robot

The robotic vehicle, Icefin, that was used for the study, was developed at the Georgia Tech lab. The team was part of a larger team of researchers from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) and the US collaborated and lived on the glacier for two months.

For Icefin to gain access to the ocean cavity, a hot water drill from BAS drilled a hole 590 meters deep (1,935-ft). It swam over 15 km in total during five missions, which also included two trips to the grounding zone. It also got as close as possible to the point where the ice met the seafloor. "We saw amazing ice interactions driven by sediments at the line and from the rapid melting from warm ocean water," described Schmidt.

A study of historical significance

The current research coincides with the 200-year anniversary of the discovery of Antarctica in 1820. Over the months and years to come, researchers from various universities from across the world who constitute the ITGC team will publish a series of studies based on the data collected during the campaign.

So far scientists have conducted research with radar and seismic measurements and employment of hot water drills to create holes at the depth of 300 and 700 meters (985 and 2,300 feet) to the ocean glacial bed under Thwaites. Samples of sediments found in the seafloor underneath the glacier were also collected and studied. They have noted that the amount of ice flowing into the sea from Thwaites and other nearby glaciers has doubled in 30 years.

"We know that warmer ocean waters are eroding many of West Antarctica's glaciers, but we're particularly concerned about Thwaites. This new data will provide a new perspective of the processes taking place, so we can predict future change with more certainty," said Keith Nicholls, an oceanographer from the BAS.