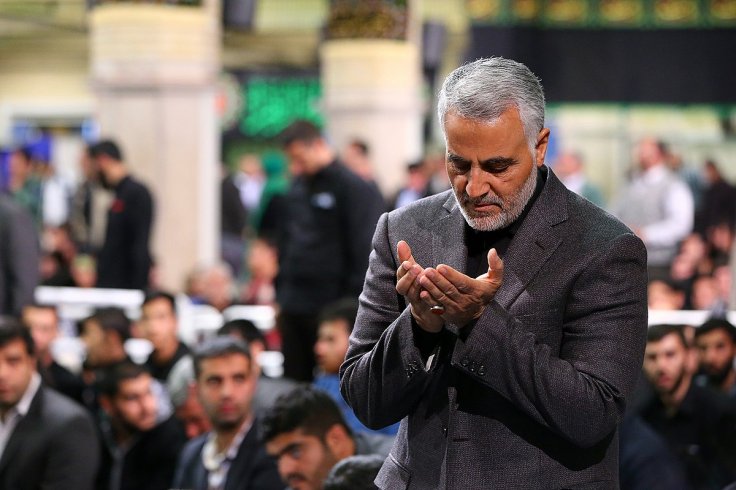

In February, an Iraqi militia commander trained by Iran took over the empty office of his slain superior, Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, killed weeks before alongside Iranian military mastermind Qassem Soleimani in a U.S. drone strike.

Many pro-Iran militiamen hoped this was the answer to their problems: the experienced commander Abdul Aziz al-Mohammedawi might replace Muhandis as overall leader of Iraq's paramilitary groups, scattered after the killing of their two mentors.

Instead, it has led to new splits.

Factions refused to recognize Mohammedawi, known by his nom de guerre Abu Fadak, as commander of Iraq's militia umbrella grouping, the Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF). Even within his own group, Kataib Hezbollah, some oppose him taking on that mantle, according to militia insiders.

The deaths of Soleimani and Muhandis in January challenged Iran-backed militias in Iraq, where the United States wants to reverse the influence of its regional foe Tehran.

Now, sources in the Iran-backed factions of the PMF and commanders in groups less close to Tehran describe growing fractures over leadership and reduced Iranian funds, thwarting attempts to unite in the face of adversity.

The rifts are accelerating a retreat from the political arena, where militia leaders who once controlled government jobs and parliament seats are in hiding for fear of assassination by the United States and confront anti-Iran dissent on the streets. They face the installing of a U.S.-aligned prime minister who signals he would check the dominance of Iran's proxy groups.

Bruised, the militias have stepped up attacks on U.S.-led forces in Iraq. Western military and diplomatic officials say this raises the prospect of a U.S.-Iran escalation Baghdad will be powerless to stop.

The focal point for the splits has been leadership of the PMF, which was formed to fight Islamic State after Iraq's top Shi'ite Muslim cleric Grand Ayatollah Ali al-Sistani called all able bodied men to take up arms against the Sunni militants.

The state-funded PMF comprises dozens of mostly Shi'ite militias with different loyalties but is dominated by powerful factions who take their orders from Iran, including Muhandis's Kataib Hezbollah, the Badr Organization, Nujaba and others.

Soleimani held ultimate authority over Iraq's toughest Shi'ite militias. But for those groups, loss of PMF military chief Muhandis, a rare unifying figure, was more significant.

GROWING DIVISIONS

Kataib Hezbollah in February announced Mohammedawi would be PMF military chief. Mohammedawi now works in Muhandis's old office in Baghdad, according to a senior militia source. He requested anonymity to talk about splits among paramilitaries.

"This created divisions, including within Kataib," the source said.

He and two other militia officials described shifting alliances, including within two pro-Iran groups. They said the splits were over both Muhandis's succession and where Iranian funds should go – into military action or political influence.

"One camp in Kataib is led by Abu Fadak. Another opposes him taking over the PMF," the first source said. "In Badr, there's a wing that supports him and was closer to Muhandis – and another that doesn't, the political wing."

The sources did not provide details on reduced funding from Iran, which is being hit hard by coronavirus and U.S. sanctions.

A PMF spokesman could not immediately be reached to comment.

The divisions mean groups are beginning to stage attacks on their own, without consulting each other, the militia sources said.

"Not everybody agreed Taji military base should be targeted," one official said, referring to an attack that killed two U.S. troops and a British soldier in March. "Some groups just operate without consulting the PMF chain of command."

The militia sources report an additional PMF split.

Several factions closer to Sistani, who oppose Iran's hegemony over the PMF, publicly rejected Mohammedawi taking over in February in a rare show of defiance of the pro-Iran camp.

Their commanders said they have since agreed in principle with the defense ministry to integrate into the military, a move that would clearly separate them from Iran-backed factions. A source close to Sistani confirmed his office had blessed the move.

POLITICAL WEAKNESS

Pro-Iran militias worry.

"If Sistani is backing this maybe 70 percent of lower-ranking fighters in all groups might follow - they joined up only because of his edict," the first militia source said.

None of those moves can be official until a new government is in place. But lawmakers and government officials say it is likely the designated prime minister, Adnan al-Zurfi, will be approved this month - a result of pro-Iran militia weakness.

"Before, the Iran-backed groups and politicians were able to get their choice of prime minister," one lawmaker from Iraq's biggest parliamentary bloc said, declining to be named.

"Now, they can't even agree among themselves who they want for the post," he said, adding many favoured Zurfi for the job.

President Barham Salih last month designated Zurfi, who is opposed by Iran-backed militia commanders. He has signaled he would come down hard on the factions, posting on Twitter in March that the PMF's "loyalty will be to Iraq, and Iraqis".

Iran-backed militias will not go quietly. Kataib Hezbollah warned last week it would fight any force cooperating with Washington in attacking militias.