Over five centuries after natives from the African continent were forcibly brought to the Americas and enslaved, researchers have found the skeletons of three such slaves in Mexico, shedding new light on the horrors faced by them.

Scientists from the Max-Planck Institute for the Science of Human History, have discovered the skeletons of three African slaves in a mass grave dating back to the 16th century in Mexico City. The study offers new insights into the lives of slaves in Latin America. It also provides evidence of colonial expansion and slave trade bringing new diseases to the region.

"Using a cross-disciplinary approach, we unravel the life history of three otherwise voiceless individuals who belonged to one of the most oppressed groups in the history of the Americas," said Johannes Krause, senior author of the study, in a statement.

Mass grave in Mexico City

The skeletons of the three individuals were discovered in a mass grave on the grounds of Hospital Real de San José de los Naturales in Mexico City, an early colonial hospital that mostly served the indigenous community. "Having Africans in central Mexico so early during the colonial period tells us a lot about the dynamics of that time," asserted Rodrigo Barquera, first author of the study.

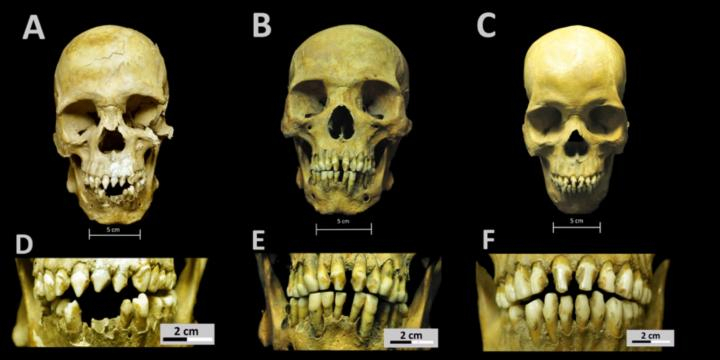

What grabbed the attention of the researchers was the distinct dental reconstruction of the three skeletons. The fillings in the upper front teeth were consistent with the recorded cultural practices of African slaves, and are still practised among certain groups living in West Africa.

Genetic analysis suggested that the persons were born in Africa and spent most of their youth there. The chromosomal evidence points towards Sub-Saharan Africa being their homeland from where they may have been abducted before being transported to the Americas. Our evidence points to either a Southern or Western African origin before being transported to the Americas," posited Barquera, first author of the study.

A life of hardships

It is no secret that slaves from Africa survived in harsh and inhuman conditions after being forcibly brought to new lands by several colonial powers of the time. Their plight and life have been documented throughout history. However, this study found physical signs of hardships faced by them, providing a window into their difficult lives.

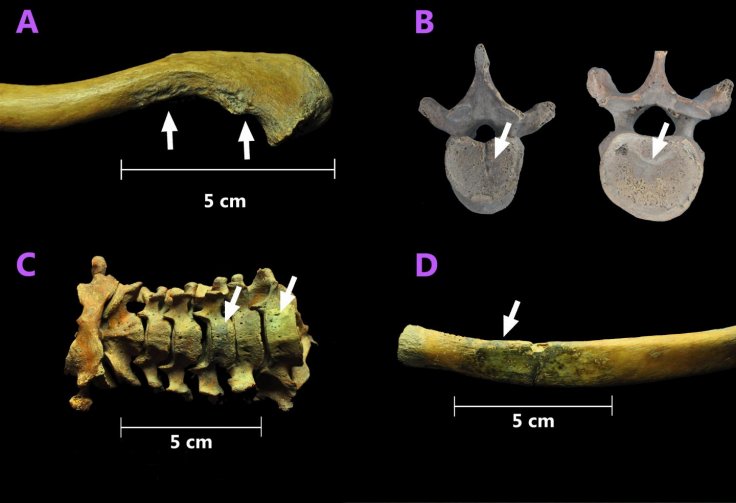

One of the skeletons was found to have large muscle insertions that were indicative of rigorous physical labour. Another person had several leg and skull fractures. Horrifyingly, the third individual had remains of a gunshot wound received from copper bullets.

The scientists gathered that while the three individuals had survived maltreatment, it did not lead to their deaths. Highlighting this finding, Barquera said, "Their story is one of difficulty but also strength, because although they suffered a lot, they persevered and were resistant to the changes forced upon them."

Slave trade and new diseases

While the researchers were able to trace the origins and ancestry of the individuals through the analysis of the genetic material collected, they were also successful in learning about the diseases that plagued them. "We found that one individual was infected with hepatitis B virus (HBV), while another was infected with the bacterium that causes yaws--a disease similar to syphilis," observed Denise Kühnert, co-senior author of the study.

Nevertheless, the examination points towards the possibility of these two individuals contracting the diseases before being brought to Mexico. The skeleton analysed in the study, are the oldest human remains in the Americas to be identified with yaws and HBV. This suggests that the slave trade could have led to the introduction of these diseases in Latin America during the early period of colonial expansion.

"It is plausible that yaws was not only brought into the Americas through the transatlantic slave trade but may subsequently have had a considerable impact on the disease dynamics in Latin America," noted Kühnert, as yaws was said to be common among Mexicans of the time.

Stressing on the potential of such studies in helping piece history together, Thiseas C Lamnidis, co-author of the study said, "Interdisciplinary studies like this will make the study of the past a much more personal matter in the future."