With the ability to cause acute sickness and even death, malaria-causing Plasmodium protozoa can be considered one of the deadliest pathogens in the world. The disease, however, is largely a seasonal one and most of the cases are known to occur during the monsoon season. Now, a new study has found that the pathogen can alter its genetic expression in order to stay hidden in a healthy person during the dry season.

According to the study conducted in Western Africa by an international team of researchers, Plasmodium falciparum can remain undetected and dormant without causing any observable symptoms and emerge when the conditions are favorable for it to thrive. "We show that low levels of P. falciparum parasites persist in the blood of asymptomatic Malian individuals during the 5- to the 6-month dry season, rarely causing symptoms and minimally affecting the host immune response," the authors wrote.

An Unforgiving Bite

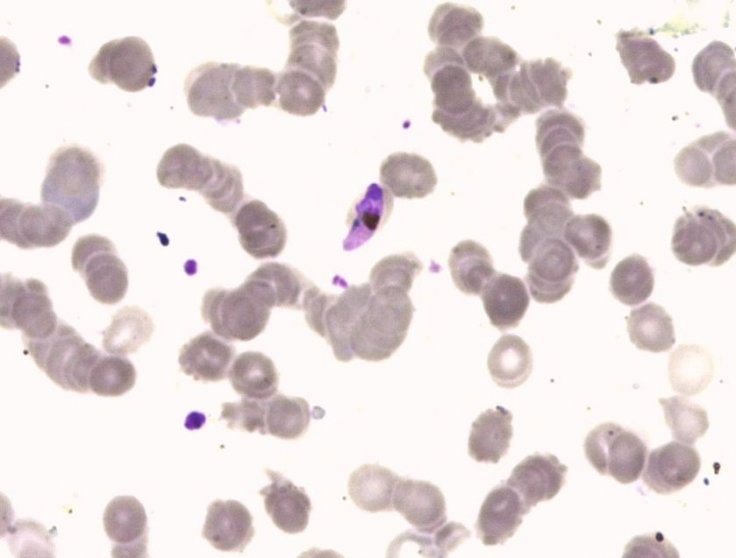

Five parasitic protozoa from the Plasmodium family, that are transmitted through the bites of vectors—infected female Anopheles mosquitoes—cause malaria in human beings. Of these, two protozoan, Plasmodium falciparum, and Plasmodium vivax, pose the biggest threats.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), P. falciparum caused 99.7 percent of infections in Africa, 71 percent in the Eastern Mediterranean, 65 percent in the Western Pacific, and 50 percent of cases in South-East Asia. P. vivax was responsible for 70 percent of the malarial infections in the Americas. Also, children formed nearly 67 percent of all Malaria deaths worldwide in 2018.

Studies have shown that P. falciparum can target a group of genes known as microRNAs, which are small molecules that play a crucial role in the regulation of genes associated with immune responses. This leads to changes in immune cells which prevent them from being detected by the immune system. The current study, however, found that the parasite also genetically alters itself to remain undetected.

Parasite Isolated During Dry Season

For the study, the scientists monitored individuals in Mali over consecutive dry (5 to 6 months) and rainy seasons. They found that P. falciparum rarely caused symptoms and affected the host immune response minimally. Most importantly, they discovered that the parasite isolated during the dry season possesses a pattern of gene transcription that was distinct.

Another interesting detail that they uncovered was that the low parasitic levels were not due to weakened replication ability. Rather, it was due to reduced binding of infected red blood cells to blood cells. This facilitated the clearance of the infected blood cells to low levels by the spleen.

"We knew that the parasite can prolong infections by continuously altering its appearance to the immune system. What this study shows is that the parasite also adopts another strategy that effectively allows it to hide in plain view by using the spleen to keep its numbers below the immune radar," said Dr. Mario Recker, co-author of the study, in a statement.

Thus, the authors concluded that these aspects promote the maintenance of a low reservoir of P. falciparum in the human body. Thereby, it avoids identification and termination by the immune system and can lead to the transmission of malaria in the subsequent favorable rainy season.