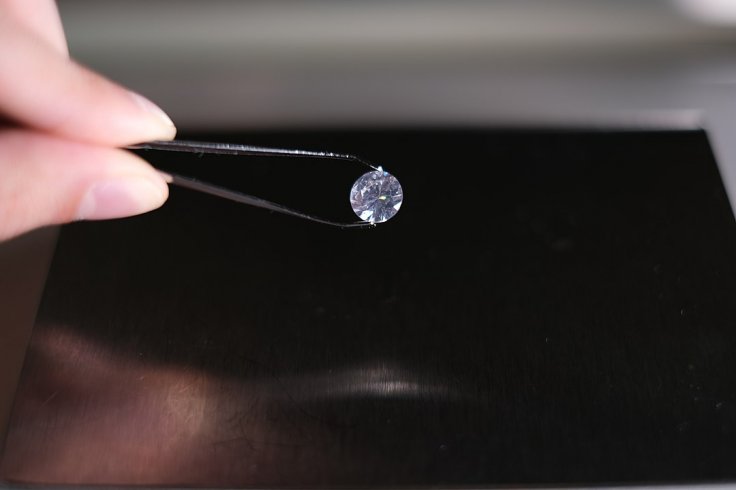

Diamond, one of the thousands of minerals found deep beneath the surface, has been the statement of prosperity for centuries. The hardest naturally occurring mineral is a woman's best friend but that it takes billions of years to form makes it one of the most precious elements on the planet. But now scientists have found a way to create diamonds in a "matter of minutes".

Since the late 19th and early 20th century, many scientists focused on making diamonds in the lab as the mineral had real industrial use and using naturally occurring ones would have cost more. But despite technological progress, growing diamonds at the lab takes at least two weeks. However, a group of international scientists from the Australian National University (ANU) and RMIT University in Melbourne (Australia), has managed to speed up the process at room temperature under high pressure.

How Did They Do It?

Naturally occurring diamonds take intense pressure and about 1,000° Celsius heat to form. Scientists had been using a similar process to create synthesized diamonds. But the researchers behind the new study said it was all about applying the right pressure. By applying pressure equivalent to "640 African elephants on the tip of a ballet shoe", scientists managed to create two synthetic diamonds— lonsdaleite and gem-grade diamonds. The former is harder than naturally occurring diamonds that are found at the meteorite impact sites.

"The twist in the story is how we apply the pressure. As well as very high pressures, we allow the carbon to also experience something called 'shear' – which is like a twisting or sliding force. We think this allows the carbon atoms to move into place and form lonsdaleite and regular diamond," Jodie Bradby, lead author of the study and a physics professor at ANU said. The findings were published in the journal Small.

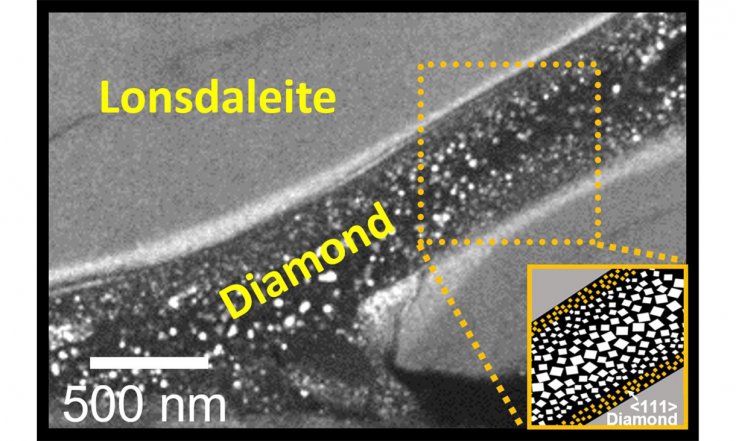

Creating lonsdaleite was only possible at high temperatures previously. But the team of scientists showed that it was possible even at normal temperature. When the team used advanced electron microscopy to better understand the process, they found that regular diamonds formed in the middle of lonsdaleite veins.

"Seeing these little rivers of lonsdaleite and regular diamond for the first time was just amazing and really helps us understand how they might form," said Professor Dougal McCulloch, co-lead author of the study.

Creating lonsdaleite at room temperature would be cheaper with the potential to use in mining machines as it can cut through ultra-solid materials. Apart from that, synthetic diamonds have had industrial use for its hardness. Synthetic gem-grade diamonds have also been preferred as a cheaper alternative to the naturally occurring ones. "Creating more of this rare but super-useful diamond is the long-term aim of this work," Professor Bradby said.