The seafaring warriors, Vikings were known for extensive trading in Europe and as far as Central Asia. But as per a new study, along with goods and weapons, they could have also carried a deadly disease.

A team of scientists has discovered the world's earliest confirmed case of smallpox in the teeth of Viking skeletons, proving that the deadly disease was widespread across northern Europe during the Viking age.

Search for the Earliest Evidence of Smallpox Disease

The ancestor of the smallpox virus is thought to have jumped from rodents to humans thousands of years ago in Africa. But written accounts and mummified remains suggested that the disease may have been present in ancient Egypt. It was also believed that the earliest case of smallpox was that of a 17th-century child, who was found mummified in Lithuania, until the new study was published.

Recently researchers have sequenced the genome of newly found strains of the smallpox virus after they extracted it from the teeth of Viking skeletons, found at the archaeological sites across northern Europe.

This new study, published in journal Science, was conducted by an international team of experts, led by Professor Eske Willerslev of St John's College, University of Cambridge, and director of The Lundbeck Foundation GeoGenetics Centre, University of Copenhagen. He said, "I think it is fair to assume the Vikings have been the superspreaders."

As per the research, Willerslev and colleagues studied the remains of 1,867 humans. During the analysis they found variola virus DNA in the teeth and bones of 11 men and women from Denmark to Russia, dating from about AD600 to AD1050. After this revolutionary finding, the lead author of the study confirmed that "it is the oldest confirmed case of smallpox."

The Variola Virus Infection

Researchers noted that these 11 individuals were likely infected with the virus when they died but it is still unclear whether the virus infection killed these individuals. However, as per the research report, one individual from Oxford seems to have had a horrific death, having been stabbed from behind, probably as part of a widespread massacre of Danes (North Germanic tribe inhabiting southern Scandinavia) or the killing of a group of Viking raiders.

The team of scientists extracted the near-complete vial of genomes from four of the remains, revealing that this now-extinct Viking age variola virus differs from modern strains, most probably evolving in parallel from a common ancestor that existed almost 1,700 years ago.

Dr. Lasse Vinner, one of the first authors and a virologist from The Lundbeck Foundation GeoGenetics Centre said the early version of smallpox was genetically closer in the pox family tree to animal poxviruses (camelpox and taterapox), from gerbils.

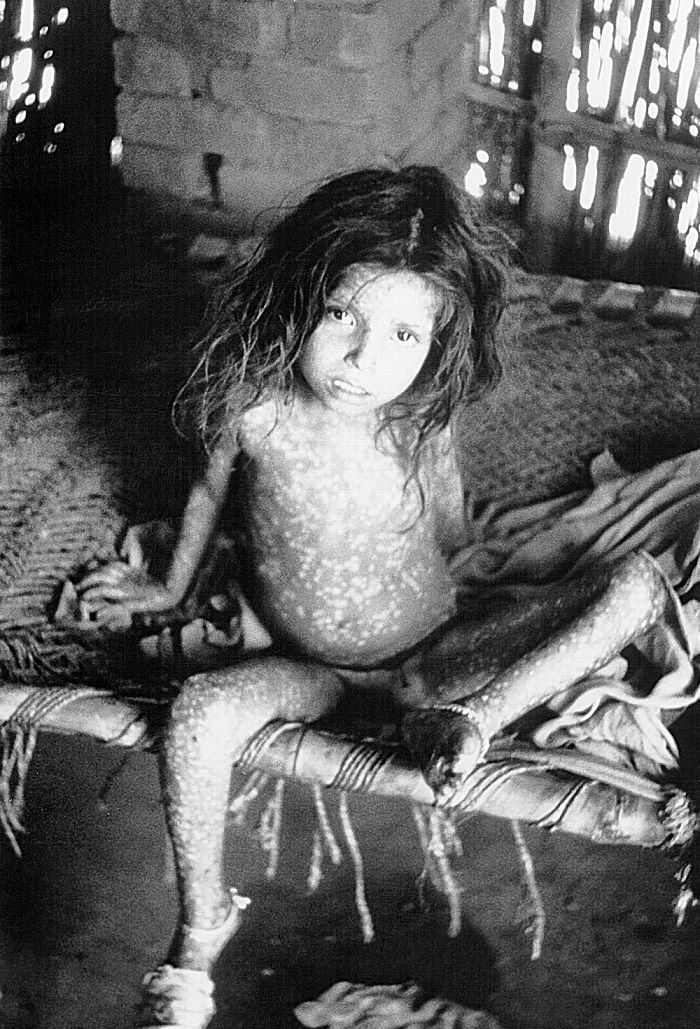

"It does not exactly resemble modern smallpox which shows that the virus evolved. We don't know how the disease manifested itself in the Viking Age -- it may have been different from those of the virulent modern strain which killed and disfigured hundreds of millions," added Vinner.

Dr. Terry Jones, another author of the study from the Institute of Virology at Charité -- Universitätsmedizin Berlin and the Centre for Pathogen Evolution at the University of Cambridge, said the finding of "smallpox so genetically different in Vikings is truly remarkable."

"It has long been believed that smallpox was in Western and Southern Europe regularly by 600 AD, around the beginning of our samples," said Jones adding that now there is proof that the disease was also widespread in Northern Europe. "Returning crusaders or other later events have been thought to have first brought smallpox to Europe, but such theories cannot be correct. While written accounts of the disease are often ambiguous, our findings push the date of the confirmed existence of smallpox back by a thousand years," he said.

Amid the current Covid-19 pandemic, the study helped to shed light on the evolution of the variola virus. Researchers believe that it could also provide clues on how other pox diseases in animals could mutate and pose risk to humans, among others.