In 1928, an event at St Mary's Hospital Medical School changed the course of medicine. It was the discovery of penicillin by Alexander Fleming, who noticed that the mould in the genus Penicillium was reducing the growth of a bacteria and that led to the discovery of the first antibiotic. Now, researchers are using the same genome once again.

Scientists from the University of Oxford, Imperial College London, and the Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International (CABI) have successfully sequenced the genome of the same Penicillium strain by re-growing it from a frozen sample. Their aim is to use the strain to fight against antibiotic resistance.

Research on the Original Penicillium

Prof Timothy Barraclough, who is from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial and the Department of Zoology at Oxford and the lead researcher of this new study, said that when they decided to use Alexander Fleming's fungus for some different experiments, they were surprised to know that "no-one had sequenced the genome of this original Penicillium, despite its historical significance to the field."

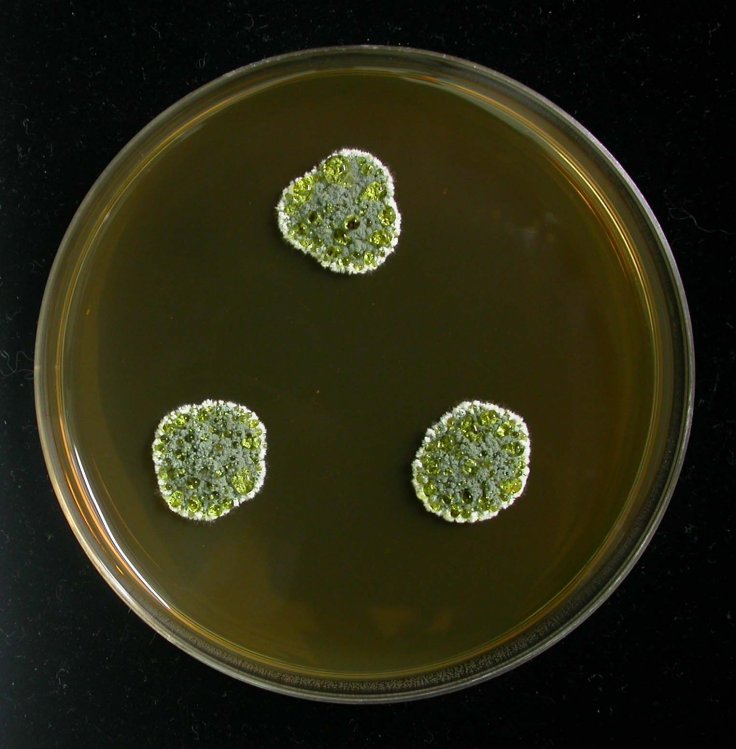

Almost 92 years ago when Fleming was working at the St Mary's Hospital Medical School, penicillin was produced by a mould in the genus Penicillium that started to grow in a Petri dish which was used to study the bacteria called staphylococcus aureus.

However, industrial production started to used fungus from mouldy cantaloupes in the US, in which the samples of Penicillium were artificially selected for strains that could produce more penicillin. The scientists compared the genomes of the original strain and two strains used recently in the US. As per their finding, which was published in Nature, there were key contrasts in the genes that code for penicillin-producing enzymes found in the distinctive fungus.

According to the scientists, this has shown that in the UK and US the wild genus of ascomycetous fungi, Penicillium, had natural evolution to produce slightly different versions of these enzymes and could help to fight against antibiotic resistance or AMR.

The first author of the study Ayush Pathak, from the Department of Life Sciences at Imperial said that recent research could help to find out a solution to fight against AMR. As per him, penicillin's industrial production is concentrated on the produced amount, and the process to artificially improve production has led to "changes in numbers of genes".

"But it is possible that industrial methods might have missed some solutions for optimizing penicillin design, and we can learn from natural responses to the evolution of antibiotic resistance," he added.

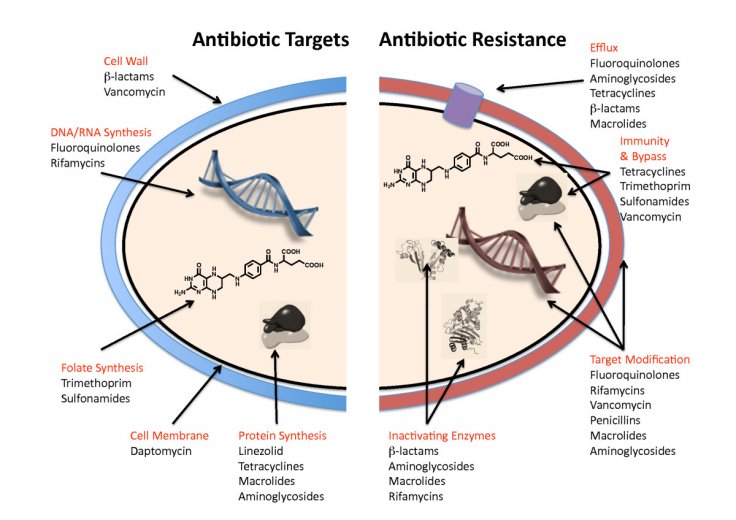

Antibiotic Resistance

This is the ability of a pathogenic microbe to develop a resistance to effective antimicrobial medication. The antibiotic resistance or AMR is now considered as an emerging threat in the world, specifically in Pacific Island nations such as Fiji.

Dr. Paul De Barro, biosecurity research director at Australia's national science agency CSIRO said that the AMR related health crisis could put modern-day medicines "back into the dark ages of health."

The AMR causes at least 700,000 deaths globally each year. But Fiji, with an extremely less population, has one of the highest rates of bacteria infection in the world. Some findings suggested that drug-resistant micro-organisms are present in the hospitals of Fiji.

Dr. Donald Wilson, the associate dean at the Fiji National University's College of Medicine has warned that AMR-related issues should not be ignored anymore otherwise more people will be affected, and currently "we don't have the right medicines to treat them."