It is astonishing what adversity can do to you. It has been eight long, painful and mortifying months for filmmaker Sanjay Leela Bhansali, master of epic sagas like "Devdas" and "Bajirao Mastani -- which have formalised his place as the only true successor to epic filmmakers such as K. Asif, Mehboob Khan, V. Shantaram and Raj Kapoor, while making an insane amount of money for him.

For the past months, while Bhansali has been attacked physically and emotionally, he has possibly felt like none of the erstwhile movie moghuls did. In fact, he feels like he is being treated like a common criminal -- hounded, threatened, bullied and heckled for a crime whose nature he isn't aware of. Perhaps, he needs to read law books which say making films in this country can be damaging to a filmmaker's health.

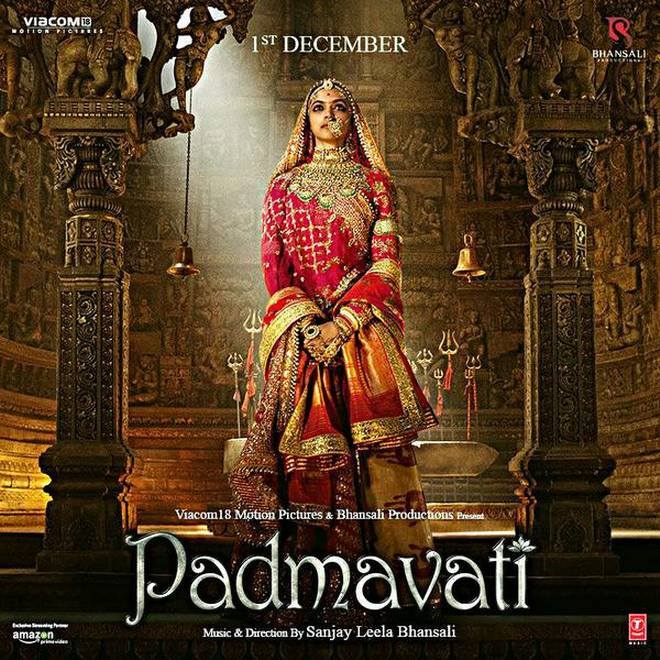

The "Padmavati" -- now renamed "Padmaavat" -- crisis appears to have broken Bhansali physically and emotionally. I know that for months he hasn't been eating or sleeping properly. And he has started chain-smoking again. "It's Lataji's songs and cigarettes which have kept me going all these months," he told me. I kept quiet. I've no words of consolation for him.

To say Bhansali has been to hell and back would be an understatement. Living under constant threat and fear is like coping with a fatal disease, one which erodes your very soul. The threats from the fringe groups -- and I've been a witness to callers on his mobile phone who have shouted that they would do much worse than behead him -- is something that no outsider would understand, let alone empathise with.

The lack of real camaraderie within the film fraternity makes it worse for someone as private as Bhansali. He became more vulnerable to attack when the bullies realised he had no support system to buffer him from them. The post-midnight calls became even more abusive.

Also, there were open offers to "stop all protests" in exchange of fiscal favours. When Bhansali shut down his mobile phone, calls began to come to his home number, sometimes attended to by his old, ailing mother.

For him, the most important thing at that moment is to protect his mother. He stopped watching news channels at home -- and once the attacks gathered momentum, the security was beefed up. He also stayed back most of the time to protect his mother against the vilification visited upon her son. But then she would get a dose of the hate campaign against him by reading the morning Gujarati newspapers that she combed regularly.

The situation at Bhansali's home appears to be very depressing. At some point, he decided to give up the fight and stopped thinking about the fate of "Padmaavat". He left the marketing decisions to his producers Viacom 18 Motion Pictures, where the executives decided to release the film on January 25.

Bhansali has become a bystander in the drama of his own that's being played out in full public view. No one is sure how this bizarre narrative based on hearsay, political antipathy and debased views will pan out. Bhansali recently asked a friend: "Can the film release in the states that have threatened to ban it? Does the CBFC endorsement mean anything to those who want to stop my film at any cost?"

One question remains, though. Why do some people want "Padmaavat" stopped? A whim, an impulse or is it something deeper than you or I could understand?

I guess, like Jessica, we'll never know who wanted to kill "Padmavati".

(Subhash K. Jha can be reached at jhasubh@gmail.com)