Our earliest forefathers, the Neanderthals, probably inhabited the island of Naxos almost 200,000 years ago, actually tens of thousands of years earlier than we had thought. The findings have been concluded based on decades of excavations, challenging what people think about human movement. For long this area was thought to be inaccessible and not inhabited until modern period humans occupied it. But now researchers are realizing that early ancestors took this complicated route, even as they moved from Africa to Europe, reinforcing their ability to adapt to new environmental challenges.

"Until recently, this part of the world was seen as irrelevant to early human studies, but the results force us to completely rethink the history of the Mediterranean islands," says Tristan Carter, an associate professor of anthropology at McMaster University and lead author of the study published in Science Advances. He conducted the work with Dimitris Athanasoulis, head of archaeology at the Cycladic Ephorate of Antiquities within the Greek Ministry of Culture.

The scholars are all part of the Stelida Naxos Archeological Project, which is a larger meet of scientists from global regions, who have been on the project since 2013. You can learn more from their website. Stone Age hunters were almost all inhabiting Europe for more than a million years. However, the Mediterranean islands were inhabited by cultivators only 9,000 years ago. It was believed that only the modern variety of humans, the Homo sapiens, could build "seafaring vessels". Scholars had also thought that the Aegean Sea, which fenced off western Anatolia, or Turkey today from continental Greece, could not be crossed by the Neanderthals and earlier hominids. The only route in and out of Europe seemed to be across the land bridge of Thrace, or southeast Balkans.

Now researchers believe that the Aegean basin could be approached earlier than they had previously thought. Sometimes in the Ice Age, the land route between the continents might have permitted the initial prehistoric populations to cross over to Stelida. There was also another migration route linking Europe and Africa. This region may even have been attractive to the early humans due to the amassed raw materials that could be used to make tools and also for the fresh water here.

Still, Carter said that "in entering this region the pre-Neanderthal populations would have been faced with a new and challenging environment, with different animals, plants and diseases, all requiring new adaptive strategies." The paper talks about human activity across almost 200,000 years at Stelida. This is a prehistoric quarry on the northwestern Naxos coast, where the initial Homo sapiens, Neanderthals and earlier humans made tools and weapons out of local stone or chert. Scientists have found thousands of their tools here.

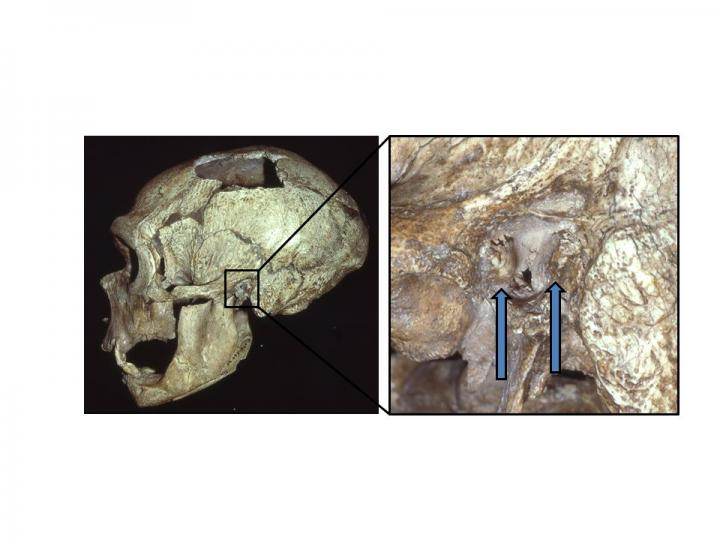

Hence, even as scientists today are convinced that the Aegean was crossed by foot 200,000 years ago, they do not rule out the possibility that the Neanderthals might have made some crude seafaring boats that could traverse the short distances. Recent findings of external auditory exostoses in the ear called "swimmer's ear" in Neanderthals reiterated their proximity to sea or water sources, according to a study published August 14, 2019 in the open-access journal PLOS ONE by Erik Trinkaus of Washington University.

Trinkaus and colleagues examined well-preserved ear canals in the remains of 77 ancient humans, including Neanderthals and early modern humans from the Middle to Late Pleistocene Epoch of western Eurasia. Approximately half of the 23 Neanderthal remains examined exhibited mild to severe exostoses, which made them conclude that these Neanderthals spent a significant amount of time collecting resources in aquatic settings.