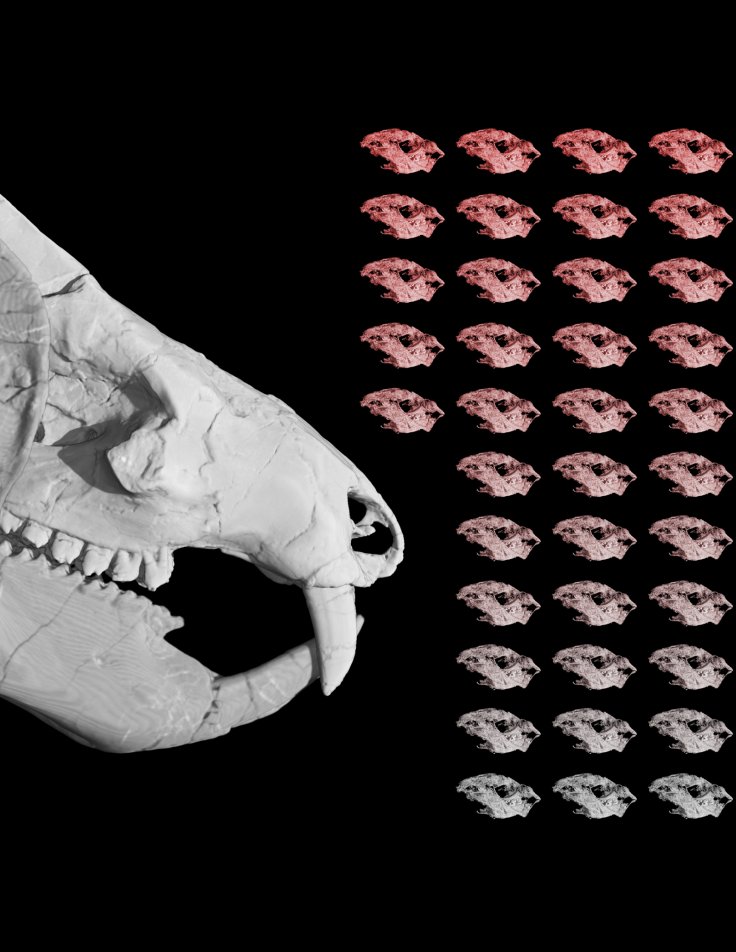

A new study has revealed that a group of scientists have discovered skulls of 38 babies, which were hidden inside ancient fossilized remains of an extinct mammal precursor. The team claimed that such fossils are the first archaeological evidence that ever discovered.

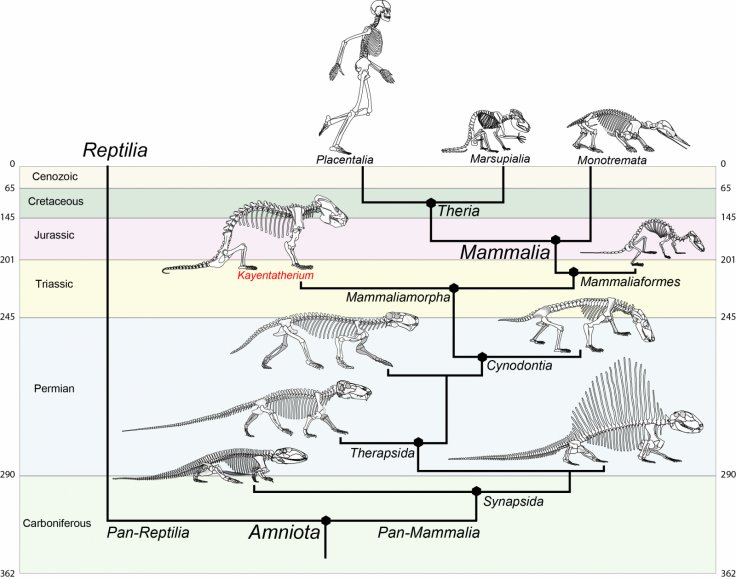

This research was presented during the 78th annual Society of Vertebrate Paleontology meeting and was published earlier this year in the journal Nature. The researchers believe that their findings may explain that how mammals swapped hordes of offspring for bigger brains the evaluation period.

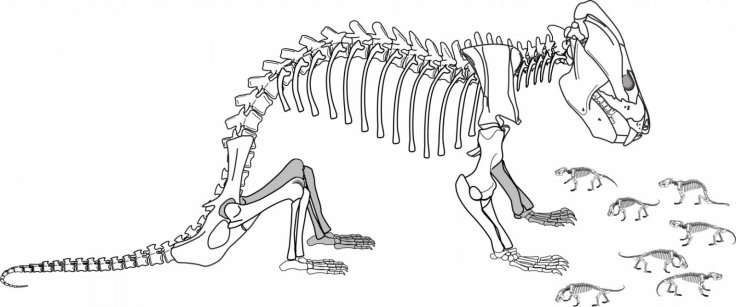

The study stated that a member of the Kayentatherium wellesi species, which is a dog-sized ancient animal that used to live on earth almost 185-million-years-ago, shares a lot of similarities with mammals and as per the researchers, it is also possible that they may have hair.

As per the archaeologists, the fossilized family has revealed the existence of an ancient animal bred, which is more like a reptile that produced a large number of eggs with lots of babies.

In addition to this, Timothy Rowe, the researcher at University of Texas said in a statement that "Just a few million years later, in mammals, they unquestionably had big brains, and they unquestionably had a small litter size."

The researchers said that the Kayentatherium's little brain and a massive clutch of children have suggested that mammals tended toward larger brain size later in their evolutionary journey.

The remains were found several years ago in Arizona but the discovery of those tiny baby skulls happened unintentionally. Almost nine years ago, then- graduate student Sebastian Egberts, who now teaches anatomy at the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine found a glint of unexplained enamel but he knew that it was neither a pointy fish tooth nor a small tooth from a primitive reptile. He said, "It looked more like a molariform tooth (molar-like tooth)—and that got me very excited."

Further research and use of imaging technology ultimately revealed the existence of those baby animals, which are a really important point in the evolutionary tree, according to Eva Hoffman, who led the research while pursuing her graduation from the University of Texas.