Close on the heels of Physics Nobel for 2019 going to exoplanet pioneers Michel Mayor and Didier Queloz, who discovered the first extrasolar planet orbiting a Sun-like star, the European Space Agency (ESA) is set to launch a first-of-its-kind exoplanet telescope to conduct deep and detailed studies of hundreds of known worlds beyond our Solar System.

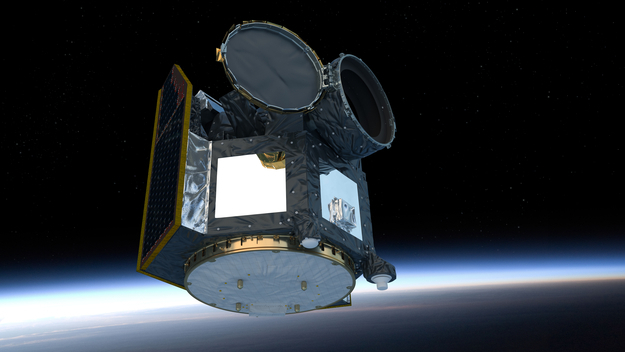

In the past, NASA, Roscosmos and ESA have launched several spacecrafts to discover exoplanets but for the first time the new telescope called CHEOPS (Characterising Exoplanet Satellite) will conduct a detailed study of about 4,000 such planets found so far.

The €50-million (US$55-million) spacecraft weighs 300 kilograms and is scheduled for launch on a Soyuz rocket from Europe's Kourou spaceport in French Guiana on Dec. 17, 2019. It will be put in an orbit of 700 kilometres above Earth, and the main instrument will point constantly towards our planet's night side without being interrupted by sunlight.

"We're moving from discovery to characterization," says Kate Isaak, a project scientist on the mission at the European Space Research and Technology Centre in Noordwijk, the Netherlands. "With CHEOPS we'll be able to answer the question of how small planets, in particular, form."

Camera specs

CHEOPS camera will peer at stars around which exoplanets are already known to orbit. It will employ the transit method to observe the dip in the brightness of a star's light as a planet passes in front of it and astronomers on the ground will use CHEOPS to estimate the sizes of these worlds and assess their atmospheres.

This study is expected to provide crucial information on the formation and evolution of exoplanets over a period of three to five years of the CEHOPS, which will begin in April 2020. The telescope will study anywhere between 300 and 500 worlds in the deeper space.

CHEOPS scientists excited

"Exoplanets have in the past 25 years become one of the hottest topics in astrophysics," says David Ehrenreich, a space scientist at the University of Geneva in Switzerland, who will be part of the ground study of CHEOPS mission. "So there's a lot of excitement in the scientific community."

It's more than three decades since astronomers discovered the first exoplanets with the help of ground-based telescopes. Later, NASA's Kepler space telescope carried out the mission uninterrupted until November 2018. NASA's next telescope Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) was launched in April 2018. Now European space telescope CHEOPS will take up the in-depth study of these exoplanets.

Not to find but to study exoplanets

CHEOPS will be the first space telescope designed to study exoplanets ranging from Earth-sized worlds to mini-Neptunes, gaseous planets that are slightly smaller than the ice giants Uranus and Neptune. Together with information about the planet masses, this will allow scientists to determine their density which provides vital clues such as indications whether it is predominantly rocky or gassy, or perhaps harbors significant oceans or not.

Some of the exoplanets in the array include the hot 'super-Earth' 55 Cancri, a suspected ice giant called HD 97658b, besides the gas giant KELT-9b, which has a dayside temperature hotter than 4,000 °C.

Launch event details

The launch event will have scientists and mission operations experts present, with live transmissions from Kourou such as liftoff at 09:54 CET, followed by Q&A sessions ahead of the Cheops separation, expected around 12:20, and announcement of acquisition of signal from the Mission Operations Centre located at INTA, in Torrejón de Ardoz, Spain will make the spacecraft a fixed mission for the study.

Future exoplanet missions

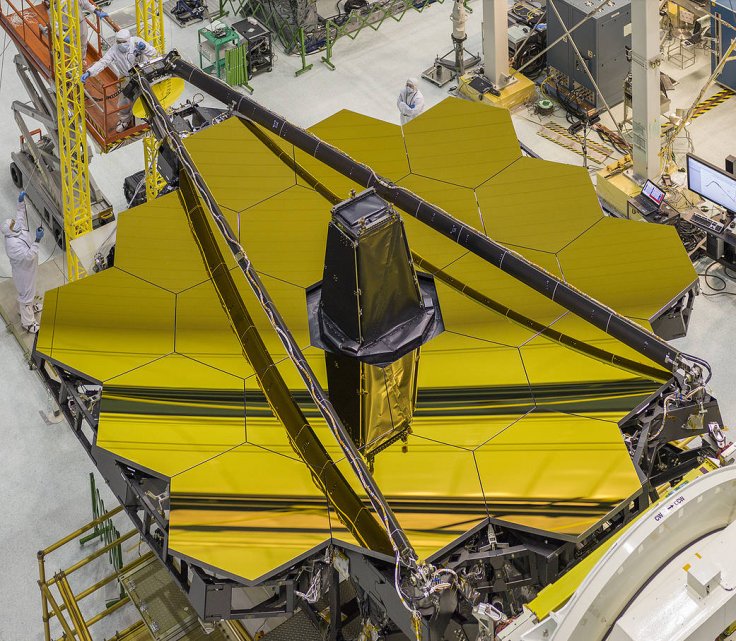

CHEOPS will be followed by NASA's James Webb Space Telescope, sometime in the mid 2020s to probe the distant Universe in the infrared part of the spectrum with its large mirror, which indeed is going to be a powerful tool.

Again in 2028, ESA will launch the Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey (ARIEL), which will study the atmospheres of about 1,000 exoplanets in infrared to determine how they evolved.

"Detecting exoplanets is now the norm," says Matt Griffin, an astronomer at Cardiff University and part of the ARIEL team. "But we need to move into a new era in which we start to characterise and measure their detailed properties."