While COVID-19 has been making headlines over the past few months, it is important to remember that other deadly diseases have preceded it and continue to exist. One such disease is Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Researchers from Rush University Medical Center in Chicago have made a startling discovery that despite treatment, HIV can stay harbored in brain cells and spread to the rest of the body again.

According to the study, HIV can hold on to brain cells known as astrocytes, and spread to immune cells within the brain and gradually to the rest of the body. This was in spite of the virus being suppressed by combination antiretroviral therapy (cART), the standard treatment for the infection.

"This study demonstrates the critical role of the brain as a reservoir of HIV that is capable of re-infecting the peripheral organs with the virus. The findings suggest that in order to eradicate HIV from the body, cure strategies must address the role of the central nervous system," said Dr. Jeymohan Joseph, chief of the HIV Neuropathogenesis, Genetics, and Therapeutics Branch at NIH's National Institute of Mental Health.

HIV And Its Treatment

The virus attacks the immune system of the body by infecting the T helper cells, which are also known as CD4 positive (CD4+) T cells. It is a type of white blood cell that aids in the functioning of other immune cells through the release of T cell cytokines. CD4+ T cells also play a role in the regulation and suppression of immune responses. If left untreated, HIV can destroy CD4+ T cells, which in turn reduces the body's ability to launch an immune response, ultimately leading to acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS)

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), nearly 38 million people are living with HIV across the world as of 2018. Patients suffering from the viral infection are treated using cART. It involves a treatment regimen that employs three or more antiretroviral drugs and is aimed at reducing the replicating capacity of the virus.

However, studies have shown that several patients undergoing antiretroviral therapy can develop HIV-related neurocognitive disorders. These include memory problems and diminished thinking functions. Nevertheless, not much is known regarding the re-release of the virus from in the bodies of those infected with it that can travel to the rest of the body and infect cells again.

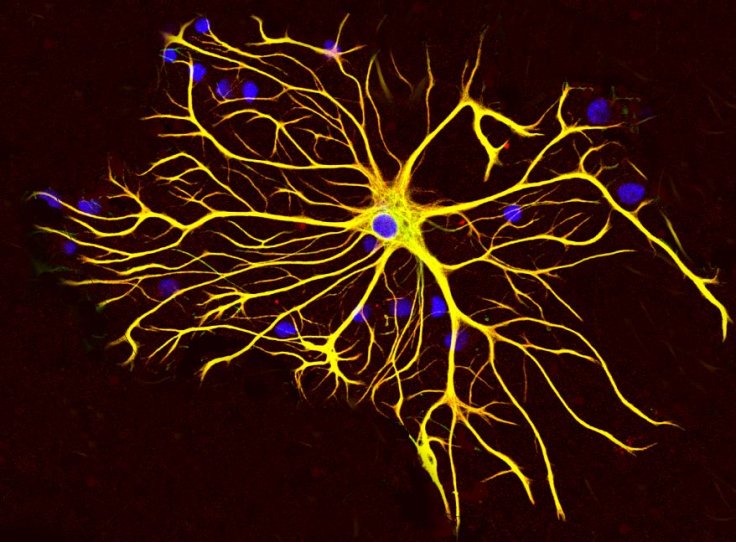

Role of Astrocytes

Astrocytes are a type of cells found in the brain. They number in billions and perform a variety of functions. The provision of nutrients to nervous tissue, facilitating communication between brain cells, and maintenance of the semi-permeable membrane known as the blood-brain barrier, are some of its functions.

In order to understand whether HIV can travel from the brain to other organs in the body, the research team transplanted noninfected or HIV-infected human astrocytes into the brains of mice that were immunodeficient.

Rebound of HIV

Confirming the doubts of the researchers, the HIV-infected astrocytes transplanted into mice were found to spread the infection to CD4+ T cells in their brains. Following this, the infected CD4+ T cells traveled from the brain to the rest of the peripheral organs in the body such as lymph nodes and the spleen, and infected them.

It was also discovered that the migration of HIV from the brain, though at lower levels, occurred even when the animals were administered cART. When the treatment was discontinued, HIV's genetic material — its RNA — was detected in the spleen. This indicated that the viral infection had indeed reemerged in the body.

"Our study demonstrates that HIV in the brain is not trapped in the brain—it can and does move back into peripheral organs through leukocyte trafficking. It also sheds light on the role of astrocytes in supporting HIV replication in the brain—even under cART therapy, " said Dr Al-Harthi, lead author of the study.

Enabling Treatment Strategies

According to Dr Al-Harthi, the findings of the study have profound implications in the treatment strategies for HIV. These strategies include the need to target and destroy reservoirs of replication of the virus and reinfection.

Emphasizing on the need for increased research in the area, Dr May Wong, program director for the NeuroAIDS and Infectious Diseases in the Neuroenvironment at the NIH's National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, said: "To help patients, we need to fully understand how HIV affects the brain and other tissue-based reservoirs. Though additional studies that replicate these findings are needed, this study brings us another step closer towards that understanding."