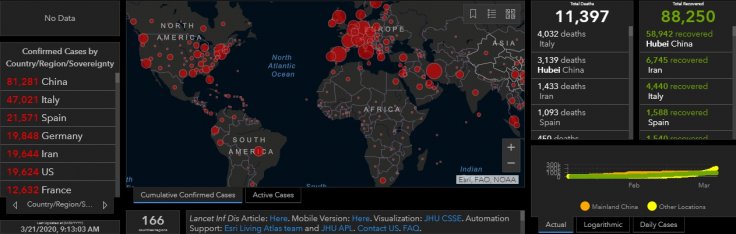

Thousands of scientists the world over are working on developing a vaccine for the coronavirus disease (Covid-19), which has killed more than 11,000 people so far. Yet, a vaccine for public use will not come before at least another year. If the virus carnage continues at the same pace as now, thousands more people would die by then. However, there's an easier and quicker, albeit temporary solution that can arrest the spread of the killer virus - passive immunization.

With more than 600 deaths reported in Italy in a single day and major parts of the US having been forced into quarantine, the virus is threatening to unleash an unprecedented health catastrophic on the world.

What is Passive Immunization?

The last few days have seen the discussion over passive immunization gaining traction. Passive immunization is a process under which antibodies extracted from the blood serum of patients who have survived Covid-19 is injected into infected people. This works out more like a 'treatment' for the virus though it's scientifically established that there is no cure as such for Covid-19.

How does passive immunization work?

When someone is infected with the coronavirus and survives the ordeal, their body will have created antibodies that give them immunity against the virus going forward. These antibodies help the body fight off another bout of the same virus attack in the future. Scientists say that these antibodies, when injected into patients suffering from the virus, give a short-term "passive immunization" to them.

Is it a proper treatment for Coronavirus?

It is not a treatment module as such but hematologists agree that it can offer a short-term solution to the virus and significantly reduce mortality. As early as February there were reports that some Chinese doctors were using the technique to treat coronavirus patients. Experts at the World Health Organization (WHO) also said the use of convalescent plasma was a "very valid" strategy. According to Mike Ryan, head of WHO's health emergencies programme, convalescent plasma is "effective and life-saving" against other infectious diseases like rabies and diphtheria.

How long will the protection stay?

The protection from the serum therapy is short-term, in the range of three weeks to one month. The patient will not develop antibodies in this method, which would be the case if he/she were to have received a proper vaccine. However, the serum therapy offers them protection in the short-term using the borrowed antibodies. The patient who fights off the coronavirus using passive immunization will be susceptible to the virus attack once the protection is exhausted.

When was it used first?

The treatment protocol named serum therapy, in which antibodies from recovered patients is used, has been in existence since 1891. It was originally tried in the fight against diphtheria. An article in The Journal of Clinical Investigation noted that the method has been helpful in stopping outbreaks of viral diseases like poliomyelitis, measles, mumps and influenza.

Is the method easy?

The challenges are basically logistical. It's learned that serum from one recovered patient can be used for the treatment of only one patient. "It's a logistical challenge to put it together, but at the very least there are no hurdles (from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration) to producing the therapy," a doctor with the Johns Hopkins University told the USA Today.

However, it should be noted that for every patient who dies of coronavirus there are at least 10 that survive. Since there are thousands of people who recover from the disease the world over, it should be possible to scale the serum therapy at a localised level in each country.

Globally, nearly 100,000 people have survived coronavirus, and that number will continue to go up in the coming days.

Will governments and health bodies explore this route?

"As we are in the midst of a worldwide pandemic, we recommend that institutions consider the emergency use (of serum from recovered patients) and begin preparations as soon as possible. Time is of the essence," Arturo Casadevall of Johns Hopkins School of Public Health and Liise-anne Pirofski of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York said in the paper.