For the first time, scientists at Stanford and SLAC have created a silicon chip that can accelerate electrons - albeit at a fraction of the velocity of that massive instrument - using an infrared laser to deliver, in less than a hair's width, the sort of energy boost that takes microwaves many feet.

Set up on a hillside above Stanford University, the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory operates a scientific instrument nearly 2 miles long. In this giant accelerator, a stream of electrons flows through a vacuum pipe, as bursts of microwave radiation nudge the particles ever-faster forward until their velocity approaches the speed of light, creating a powerful beam useful to probe the atomic and molecular structures of inorganic and biological materials.

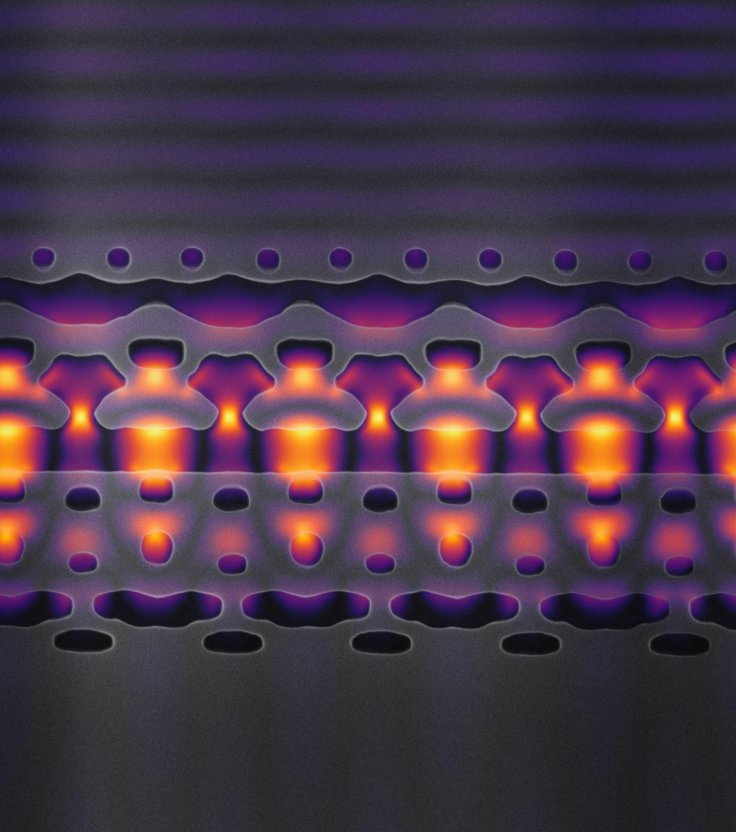

In their paper published in the Jan. 3 issue of Science, a team led by electrical engineer Jelena Vuckovic explained how they carved a nanoscale channel out of silicon, sealed it in a vacuum and sent electrons through this cavity while pulses of infrared light - to which silicon is as transparent as glass is to visible light - were transmitted by the channel walls to speed the electrons along.

The accelerator-on-a-chip demonstrated in Science is just a prototype, but Vuckovic said its design and fabrication techniques can be scaled up to deliver particle beams accelerated enough to perform cutting-edge experiments in chemistry, materials science and biological discovery that don't require the power of a massive accelerator.

Accelerators are like powerful telescopes

"The largest accelerators are like powerful telescopes. There are only a few in the world and scientists must come to places like SLAC to use them," Vuckovic said. "We want to miniaturize accelerator technology in a way that makes it a more accessible research tool."

Team members liken their approach to the way that computing evolved from the mainframe to the smaller but still useful PC. Accelerator-on-a-chip technology could also lead to new cancer radiation therapies, said physicist Robert Byer, a co-author of the Science paper. Again, it's a matter of size. Today, medical X-ray machines fill a room and deliver a beam of radiation that's tough to focus on tumors, requiring patients to wear lead shields to minimize collateral damage.

Medical application to beam radiation directly to a tumor

"In this paper we begin to show how it might be possible to deliver electron beam radiation directly to a tumor, leaving healthy tissue unaffected," said Byer, who leads the Accelerator on a Chip International Program, or ACHIP, a broader effort of which this current research is a part. It can derive medical benefits from the miniaturization of accelerator technology in addition to the research applications, explained researchers.