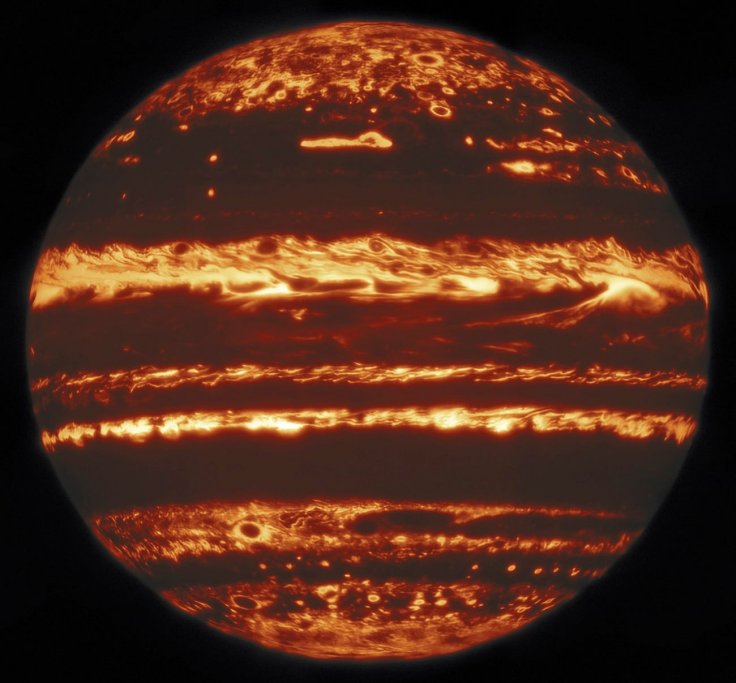

A group of researchers was able to capture the sharpest infrared photo of Jupiter taken from Earth. According to the researchers, the planet looked like a flaming jack-o-lantern in the new image. Jupiter's latest image was taken by researchers from the University of California and NASA. A study regarding the image they took was published in The Astrophysical Journal.

Taking A Clear Photo Of Jupiter

The researchers were able to snap a photo of Jupiter using the Gemini North Telescope in Hawaii. Through the telescope's infrared imaging capabilities, they were able to spot the planet from Earth. The researchers then refined the image using a technique known as lucky imaging. This involves removing the blurring effect of looking out through Earth's atmosphere. They then combined the image with those taken by NASA's Hubble Space Telescope and the orbiting probe Juno to produce the sharpest image of Jupiter ever taken.

Jupiter As A Jack-O-Lantern

The resulting image provides a different perspective on the planet. Since it is not obstructed by the atmosphere, the bright features of the planet can be greatly seen. These include the bands that appear across the planet. According to Michael Wong, the lead author of the study, the regions on Jupiter that normally appear dark under visible light appear bright in infrared. This indicates that the areas that are usually dark in visible light could be holes in the cloud layer of Jupiter.

Through the lucky imaging technique, the researchers were able to highlight the contrast in these bright and dark regions. As noted by Wong, through infrared light, Jupiter looks like a massive burning jack-o-lantern. "It's kind of like a jack-o-lantern," he said in a statement. "You see bright infrared light coming from cloud-free areas, but where there are clouds, it's really dark in the infrared."

Learning About Jupiter's Weather

Amy Simon, a planetary scientist for NASA, noted that the high-resolution images of Jupiter could provide valuable information regarding the planet's atmospheric conditions. "Because we now routinely have these high-resolution views from a couple of different observatories and wavelengths, we are learning so much more about Jupiter's weather," she stated. "This is our equivalent of a weather satellite. We can finally start looking at weather cycles."