A team of researchers from the Smithsonian's Global Health Program have discovered six entirely new coronaviruses in bats found in Myanmar - the first time these viruses have been detected anywhere in the world.

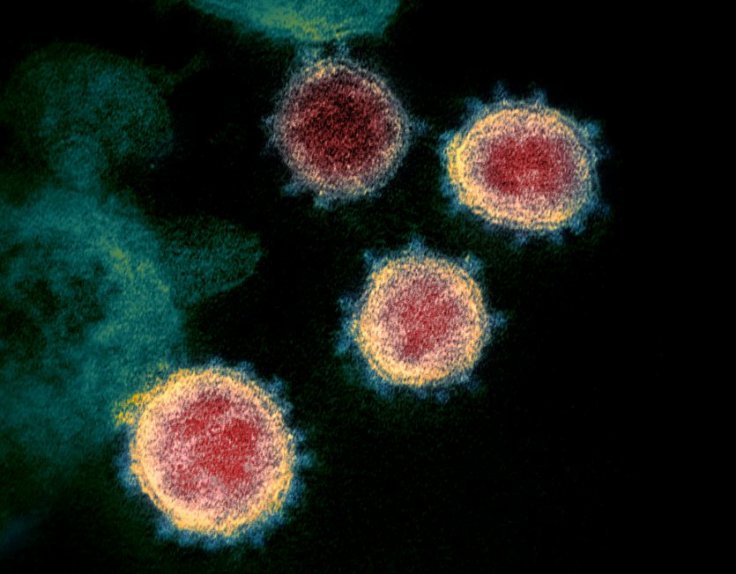

These viruses belong to the same family as the SARS-CoV-2 virus that is currently spreading rampantly across the world, infecting more than 1.7 million people and killing over 1,00,000.

Viruses are from the SARS-CoV-2 family

The researchers found the viruses while doing research on bats in Myanmar during a US government-funded program called PREDICT. The program's aim is to identify infectious diseases that have the potential to be transmitted from animals to human beings.

Bats were used as subjects as the flying mammals have been known to host thousands of yet-to-be-discovered coronaviruses. SARS-CoV-2, which caused the COVID-19 outbreak, is also believed to have been carried by bats before being transmitted to humans, the researchers noted in their study published on Thursday in the journal PLOS ONE.

The team collected hundreds of samples of saliva and faeces from 464 bats belonging to at least 11 different species and found the new viruses in three bat species - the Greater Asiatic yellow house bat, where they found the PREDICT-CoV-90 virus, the wrinkle-lipped free-tailed bat, which was host to the PREDICT-CoV-47 and -82 viruses, and Horsfield's leaf-nosed bat, which was carrying the PREDICT-CoV-92, -93 and -96 viruses.

Are these viruses deadly?

While the researchers believe while these newly found coronaviruses are from the same family, they are not closely related in the genetic sense to SARS-CoV-2 or the two other deadly coronaviruses that infect humans - severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which caused the 2002-2003 pandemic, and Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS).

That said, the researchers pointed out that the threat level of these viruses is not yet known and further research will be required to fully understand the potential for these six novel coronaviruses to be transmitted to other species and their impact on human health in order to prevent an outbreak in the future.

"Many coronaviruses may not pose a risk to people, but when we identify these diseases early on in animals, at the source, we have a valuable opportunity to investigate the potential threat," study co-author Suzan Murray, director of the Smithsonian's Global Health Program, said in a statement. "Vigilant surveillance, research and education are the best tools we have to prevent pandemics before they occur."

The study adds that it is essential to understand what allows these viruses in animals to mutate and how they spread to other species in order to reduce their potential of causing a global pandemic like COVID-19.