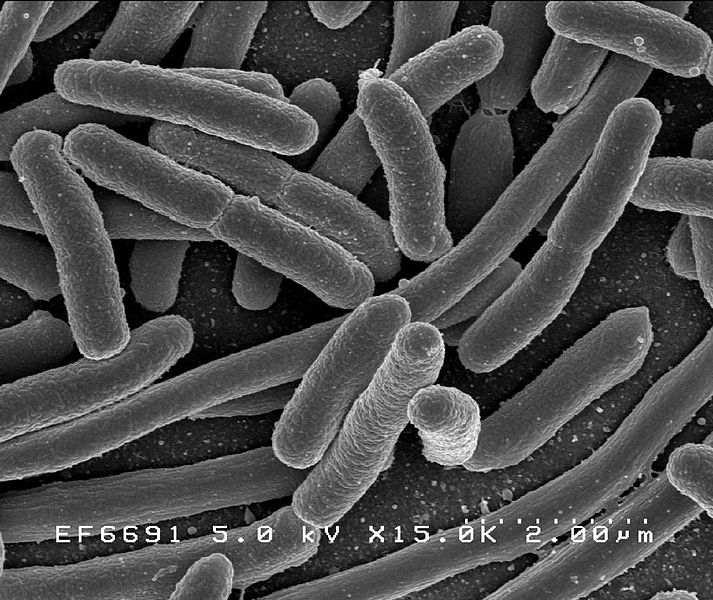

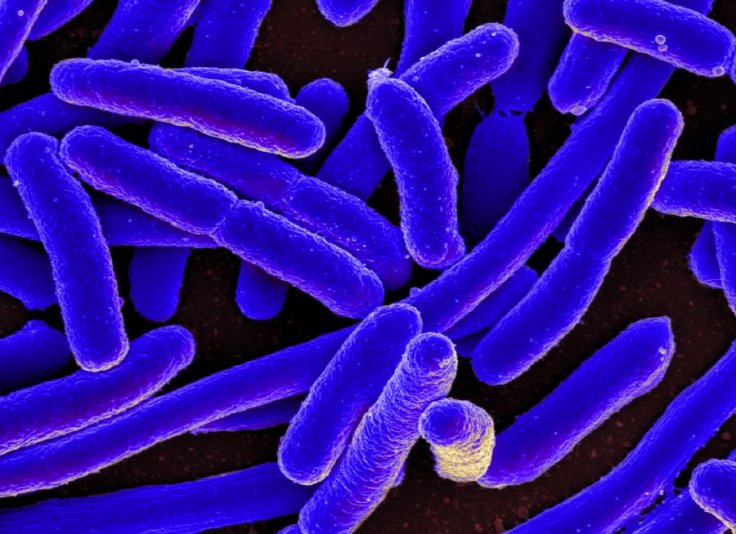

While most strains of Escherichia coli (E.Coli) bacteria are harmless, some of its strains can cause life-threatening diseases. A new study by researchers from the University of Cincinnati offers evidence that a harmless strain of the bacteria may offer protection from a lethal one. According to the study, Nissle—a strain of E.Coli that is used as a probiotic—was found to protect human intestinal organoids (HIOs) from a pathogenic strain known as enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC).

The researchers began by injecting HIOs—intestinal tissues generated from stem cells—with Nissle and found that it was harmless. It caused no damage to the outer protective layer of the organoid, leaving the epithelial barrier unharmed.

Next, EHEC that produces a toxic compound called Shiga toxin that causes conditions such as bloody diarrhea, were injected into the HIOs in separate experiments. However, the epithelial barrier of the organoids was quickly broken down.

Pitting 2 Strains of E.Coli Against Each Other

Following this, the researchers treated HIOs with Nissle and injected EHEC into the pre-treated organoids. The Nissile, however, provided protection to the HIOs. Despite the organoid tissue seeing rapid multiplication of the EHEC, the epithelial was not destroyed.

Similar results were observed when the scientists injected uropathogenic E. coli— a strain that causes infection of the urinary tract—into pre-treated HIOs. Alison Weiss, the co-author of the study, explained, "Basically, the Nissle was killed by the pathogenic bacteria, but it made the intestine able to withstand damage better."

Therapeutic Application Requires Study

The protection provided by Nissle is not direct as it does not inhibit the lethal strain. Rather, it uses the cell's defense mechanism itself. Therefore, it may serve as a preventive option of keeping severe EHEC infections at bay. However, the study also highlighted that the probiotic is not invulnerable to the Shiga toxin produced by its toxic cousin. This limits the possibility of its use as a therapeutic. Weiss added that the complex interactions between the two strains of bacteria require further study.

Emphasizing on the potency of bacteria that produce Shiga toxin, Weiss said, "It's really bad. My whole career, I've been interested in preventing pediatric pathogens. Once these kids get EHEC, all you can do is give them fluids and support them. There's nothing else we can do."

Conveying her excitement over the use of HIOs as models to study intestinal conditions, Weiss averred that the stem-cell generated tissues are a "huge breakthrough". She concluded, "A lot of intestinal pathogens are species-specific, and organoids are really good for looking at early events."