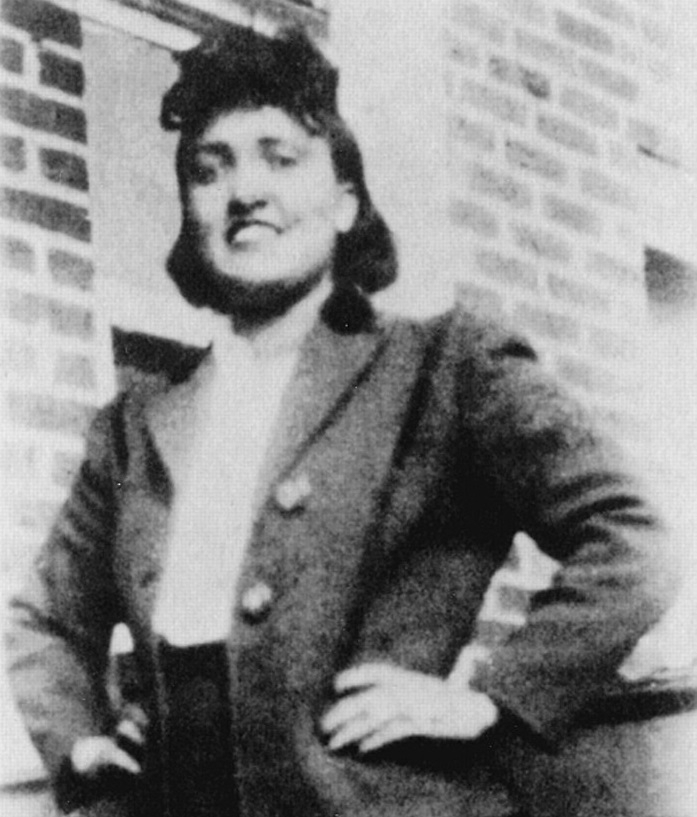

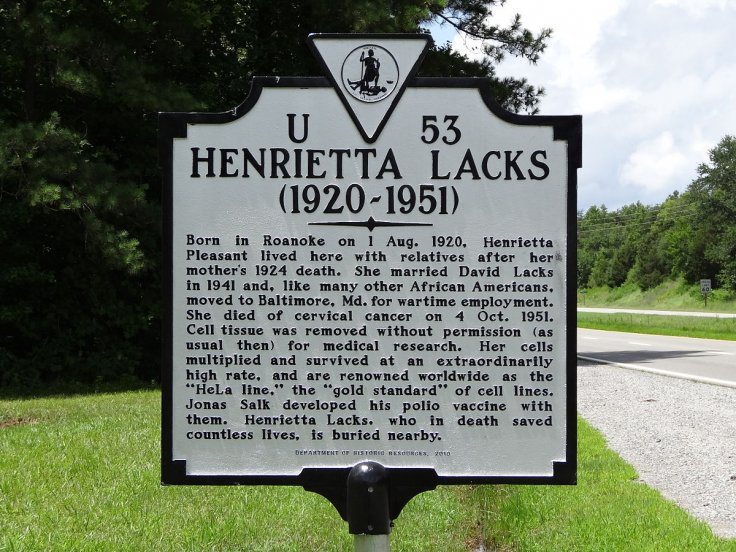

Henrietta Lacks is considered 'the mother of modern medicine' even though she never had a medical degree. In short, she was an African-American tobacco farmer, who mothered five children, died of cancer at the age of 31 in 1951.

That was her life story. And if you haven't heard her name, you could be forgiven as until after her death, she wasn't of significance to people outside her family. But she was immortalized after death. On her 100th birthday, let's try to find out why she became such a revered name in the medical community.

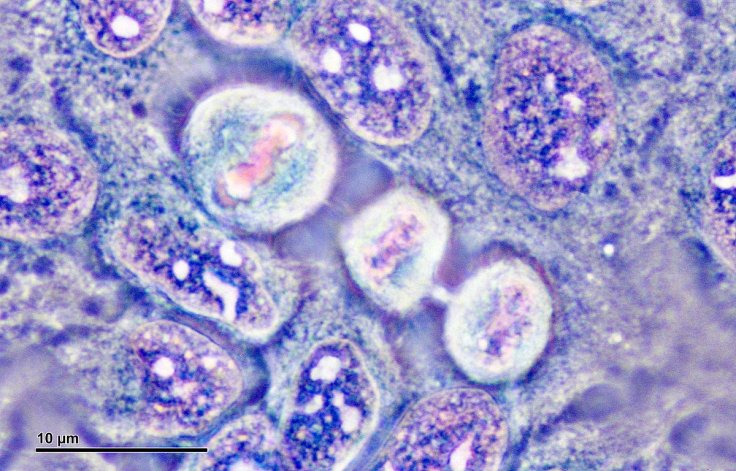

Immortal HeLa cells

Her story first came into the spotlight in 2010 when Rebecca Skloot published a book titled, 'The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks'. In the book, Skloot narrated the life of Lacks and her contribution to medical science.

After complaining of abdominal pain and bleeding following the birth of her fifth child, Lacks was admitted to Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore. Doctors extracted tissue from her cervix for a biopsy and diagnosed cancer. A small part of the tissue was also taken to the cultural laboratory and it stayed there without being noticed.

But cancer researcher George Gey found the samples and made a monumental breakthrough realizing that Lacks' cells were not of an ordinary kind. Henrietta Lacks' cells — HeLa cells — despite being put in an artificial environment of that time, didn't die. Instead, it replicated at an unheard-of rate of that time.

Cells are preserved in an artificial environment to create models and study their growth for creating vaccines and drugs. Outside its natural habitat (a living body), during that time, cells were artificially kept alive using the blood of chickens, special salts, and placentas.

But even then, Dr. Gey's efforts were not really successful. While he was able to keep some of the animal cells alive, he didn't have much success with human cells, although some of them showed promise.

But HeLa cells were unique and became the first immortal cell line that helped in research for AIDS, polio vaccine, IVF therapy, gene mapping, and even COVID-19. Her cells even traveled to space as a part of a study to understand the effects of microgravity on cells.

Controversy Surrounding Research

Despite the advances, Dr. Gey made and helped in the research, Lacks' family was not aware of her cells being kept alive. It was in 1973 when Johns Hopkins hospital approached Lacks' family to draw blood samples for further study, they came to know about the existence of the cells. They never consented to the research and use of her cells — a common practice of that time.

Dr. Gey, although, supplied the cells nationally and internationally without making a profit, he never gave credits to Lacks' family. But HeLa cells became the foundation of a multi-billion-dollar industry with over 17,000 patents with her family receiving no compensation or recognition.

Furthermore, in 2013, the European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Germany published the HeLa genome sequence without the consent of her family. That raised ethical questions. Her descendants argued that it could reveal the genetic traits of the Lacks family, something that should be kept private.

Following the controversy, EMBL reached a compromise with the family, agreeing to the 'HeLa Genome Data Use Agreement'. Now, two members of the Lacks family oversee the use of the cells and grant permission as members of the U.S. National Institutes of Health. Privacy is a major concern in the medical field and thus cells have been anonymized to preserve patients' rights.

Recognition

Almost 45 years after her death, Lacks finally received recognition when Morehouse School of Medicine held its first annual HeLa Women's Health Conference in 1996, led by Professor Roland Pattillo. Shortly after that, the mayor of Atalanta, the U.S., declared the date of the conference as the 'Henrietta Lacks Day'.

In 2010, Pattillo, donated a gravestone in her memory with inscriptions, "Here lies Henrietta Lacks (HeLa). Her immortal cells will continue to help mankind forever." Pattillo also worked with Dr Gey and knew the Lacks family.

In 2011, Morgan State University in Baltimore granted Lacks a posthumous doctorate in public service besides many other recognitions from universities. In 2017, Kadir Nelson painted a portrait of Lacks as a part of HBO's film titled the same as the book by Skloot.